1. Introduction

Modern education standards, both general and foreign language, set complex goals that learners need to achieve at different levels. In addition to subject-specific goals, the importance of key (general or universal) competences and personal qualities is especially emphasized. However, in education standards in different countries as well as in pedagogical research papers educators use different terms to define similar competences and skills. We can come across such terms as «key» [1], «general» [2], «generic», «meta-subject» [3] «universal» [4] competences and «soft skills» which are very close in meaning. All of them are described as those that have multiple areas of application, being transversal and used in multiple areas of life. Therefore, «soft skills should be thought of as part of cradle-to-grave learning, insofar as they need to be developed at every stage of curricula and beyond» [12, p. 23]. In the context of the article, we use these terms interchangeably.

In sum, along with hard skills, the core aspects which every student is supposed to be skilled at are communication, collaboration, thinking, emotional management, information management, and PC application. Taken together, these skills promote constructive and effective decision-making and problem-solving concerning some specific content and context wherever and whenever they are required. Indeed, modern education appears to be multifunctional and multifaceted. Society and businesses expect it to prepare every learner to become a competent agent in a great variety of diverse activities, being able to initiate them (value and motivational aspect), to plan and perform them, using appropriate resources and tools (metacognitive and instrumental aspect), to analyze, synthesize and evaluate or produce relative content (information processing and higher-order thinking aspect), to monitor, assess and reflect on the outcomes of the activity and one's contribution (reflective aspect).

Though all education standards as well as curricula set integral goals, a lot of controversies still exist both in theory and in educational practices.

The first challenge is related to the fact that very often, educational institutions teach to tests that learners have to take on completing this or that course [15]. Such tests check students` knowledge and hard (specific, professional) skills. Part of the reason is that it is not easy to assess and measure the level of soft skills [12, p. 18; 27]. Moreover, universal competences are developed and manifested in diverse human activities and contexts. They are always adjusted to some specific content and used by an individual person, each time acquiring unique features. Thus, it is not easy to grasp their essence and describe the conditions and particular strategies of their development.

Doing the study, we also noticed that a great bulk of research mostly focuses on fostering each soft skill separately as a specific objective (for example, communication or critical thinking). As a result, the teaching process loses cohesion and integrity and looks like student hopping from one goal to another. Moreover, focusing on the development of each soft skill is time-consuming. For all of these reasons, it may be difficult to create a whole picture of the teaching and learning process and see the links between the goals and outcomes.

The achievement of any goal implies that there are special tools used under specific conditions, all of which are relevant to the goal. Consequently, the present study is an attempt to elaborate such educational tools and investigate the essentials of how to apply them effectively. Based on the multifunctional character of modern education, we argue in favor of multifunctional tasks as didactic tools that can, to a high degree, facilitate the integration of varied skills (subject-specific and general/soft) in teaching and learning foreign languages. We define multifunctional tasks as intentionally designed purposeful learners' activities that mobilize and enhance a variety of experiences (knowledge, skills, and values), and result in the achievement of a set of integral outcomes of language education. Their characteristic features, therefore, are: focus on achieving several interrelated results (subject-specific, general, or universal, and personal) on the way to the final product; emphasis on cognitive and higher-order thinking processes in information processing as well as on self-regulating, self-monitoring, and reflecting to be successful in any activity; sequence of interconnected sub-assignments directing the students` steps in performing the «big task», shifting student attention in turn either from the language form to its meaning, or from facts to some message or opinion; recycling both language items as well as a set of varied generic operations (strategies) concerning the topic under discussion, each time focusing students on a different sub-goal; personalizing the topic, which suggests expressing and discussing the students` real experiences, thoughts, feelings, and attitudes in the course of the task completion, interacting with others. To accomplish a multifunctional task, learners need to move from a learning activity to some interrelated communicative and cognitive (thinking) actions; they need to incorporate verbal actions into other activities (games or projects or drama or research or debates, etc.). It is evident that, while doing so, learners are supposed to draw on more than one skill or competence.

The tangible outcomes of multifunctional tasks present the learners' texts (oral or written, monologues or dialogues in a discussion or debate or project presentation, etc.), which are sometimes accompanied with some visual product (a poster, a spider-web, a mind map, a brochure, a presentation or a video). The final texts are based on the accumulated information received from different sources (texts, videos, interviews, personal experiences, or through interaction with others) and then analyzed by the students (cognitive skills such as pointing out characteristics, classification, comparison, generalization, etc.), presented in a well-structured way (defining the structure of the text and varied links among its parts, finding cause and effect, distinguishing facts and opinions, elaborating a spider-web, etc.), interpreted (providing reflections and arguments) and evaluated (providing personal evaluation and final well-reasoned opinions). The integral intangible result of multifunctional tasks, therefore, is a change in the learner's personal experience viewed from a broad perspective.

To design an effective multifunctional task, teachers can combine a variety of techniques, such as «diversity of students – diversity of materials» based on pair work and mingles [6], thus encouraging learners to exchange information; «flipped classroom» [42] when students do part of the task at home (read a text, watch a video or write a report); brainstorming [28] for a variety of ideas, solutions or arguments; graphic organizers [13; 33], which help learners structure information and define links, etc. All of them promote the student transition to the position of the agent of both learning and interacting with others in a foreign language while fulfilling the whole task. Through such techniques, students are expected to gradually develop the ability to use a foreign language as a means of communication, reflection (generating and expressing thoughts), and human collaboration in many spheres of life. These language and communication functions are realized through varied speech acts incorporated into different types of human activities (work, study, games, leisure, arts, projects, etc.) [16; 17]. The assumption is that effective language acquisition occurs provided there are appropriate conditions for its multifunctional application in different activities. That is why the overwhelming majority of language education tools, including tasks and exercises, are inherently multifunctional even if they are used with a single specific purpose in mind.

Consequently, the authors posed the following research questions: why and on what condition do multifunctional tasks serve as efficient didactic tools to achieve integral outcomes in varied contexts of university foreign language education? We elaborated a set of multifunctional tasks that were incorporated into university classrooms for different groups of students with a wide range of foreign language levels, all future teachers of language and non-language subjects. However, more research is needed to find further evidence and explore the effects of multifunctional tasks in foreign language education.

2. Literature Review

Analyzing the literature concerning foreign language education, we conclude that the issue of developing soft, or general, skills has been directly or indirectly considered by researchers. All researchers in this field single out communication as a priority for the development of foreign language communicative competence which is considered to be a subject-specific goal, as well as the central task characteristic and condition of foreign language acquisition with a focus on meaning [8; 21; 29; 35]. Researchers also stress the importance of interaction, collaboration, and problem-solving as major task conditions which facilitate the development of the target competence or its components [10; 11; 24; 25; 35; 38], promoting the integration of all language skills [30]. A lot of studies claim that foreign language tasks can enhance learners` critical thinking skills provided they meet certain requirements [18; 19; 23; 26]. Another indispensable aspect of modern foreign language education – intercultural communication competence - also implies the achievement of integral goals.

Recently, more papers have appeared where researchers emphasize interconnected foreign language skills and soft skills development [22; 34; 39; 41]. If we look into the new version of the Common European Framework of Reference [2], we can see that the document draws attention to the importance of the interrelated development of general and foreign language communicative (subject-specific) competences as a prerequisite for effective foreign language learning.

The well-known ESP or LSP (English or Language for specific purposes) courses or the Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) also implement the integrated teaching and learning of both a foreign language and professional subject-specific content (the English language for mathematics, lawyers, tourism, etc.) [5; 14; 37]. Both ESP and CLIL models appear to be multiple-focused in their nature. Kic-Drgas (2018) emphasizes the tight relationship between soft skills and language function, understanding soft skills «as an ability to handle strategies for implementing foreign language and subject content knowledge in a professional environment, in order to cope with professional tasks».

In sum, to meet the modern education standards requirements and qualify as a competent foreign language user, every learner is supposed to develop integral outcomes, which include: language-specific sub-skills and skills (communicative language competences); the general (universal/key and metacognitive) competences; personal values and traits (often described as soft skills) [2; 40]. As the designers of the CEFR underline, «language use, embracing language learning, comprises the actions performed by persons who as individuals and as social agents develop a range of competences, both general and in particular communicative language competences» [2, p. 29]. Personal features and values are also regarded as essential components of language education aims [20; 35]. The most important personal value fostered in foreign language communication is the value of every human being which is reflected in respectful treatment of others, their opinions, and beliefs. [36; 38].

The positive impact of the consolidated development of varied skills and competences in foreign language education has been vividly grounded by a range of research papers (R. Oxford, L. F. Bachman, A. S. Palmer, E. I. Passov). Li and Shirley Larkin have revealed that special teachers' focus on the development of metacognitive knowledge and strategies, primarily while planning, performing and monitoring activity, as well as while assessing its results, has a significant impact on the quality of language acquisition outcomes, particularly on reading and writing skills [18, p. 11].

A few Russian researchers draw attention to specific tools that can promote integral outcomes of foreign language education. In their papers, they describe «multifunctional exercises» which are aimed at reaching both subject specific and generic goals [7; 8; 9; 27]. In the context of the present study, the idea of «rich tasks» suggested by Ferguson especially appeals to us. She characterizes them as those which provide an intellectual challenge (in both content and processes) for students focusing them on «exploration, thinking, reasoning, articulating ideas and arguing, using visual representations, discussing core concepts as a community» [32, p. 35].

Thus, as seen from the literature review, modern pedagogy, as well as foreign language teaching methodology, prioritizes those aims, conditions, and tools which, along with specific skills, promote the student whole-person development. Nevertheless, a major limitation with up-to-date research is that there has been little focus on particular didactic instruments that can allow for cumulative learning outcomes in the field of foreign language education. In most cases, task functions are mainly limited to some subject-specific results of language education (speech skills and language sub-skills).

Therefore, we conclude that to achieve the complex aims of university foreign language education, we need to develop special educational tools.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Methods

During the initial phase of the research, the data were obtained by means of qualitative methods: (a) through the analysis of the existing approaches to the use of varied tasks in foreign language university education and multifunctional tasks in particular; (b) through classroom observations and analysis of the results of classwork; (c) through conducting a questionnaire with open-ended questions among the student participants in the project (81 respondents) which was designed to find out the students' attitudes to learning foreign languages in the previous years of education; (d) through gathering data related to the university context of foreign language teaching and learning. The overview of the data gathered in the initial phase allowed us to articulate research questions for the project and to outline a few solutions to consider in the study.

The implementation phase of the study consisted of two parts: the design of Part 1 was based on conventional tasks sequenced according to the PPP model (presentation, practice, production). Some of them emphasized general/universal skills. Part 2 included a few multifunctional tasks.

The final phase consisted of the analysis of the results obtained.

The factors in the study that were not changed in each part were the number of classroom hours per week and the total time allocated to the discussion of every topic.

The factors that were reexamined in the course of the study (Part 1 and Part 2) were: (a) the content of the course (different topics); (b) classroom techniques.

At the end of each part, the students did problem-solving tasks based on the topic. The length of each part was 10 classroom hours in October – December 2019.

Quantitative methods were used to assess the students' performance in the PPP model and the multifunctional task-based learning model. Four criteria based on universal competencies and one criterion related to communicative competence were developed and described to assess the students' performance. The data gained in the study were analysed and Chi-square statistics was used to prove the correlation between the model used and the results achieved.

3.2. Research ethics

Prior to the collection of the data, all participants were informed of the research and its aims. They expressed their willingness to participate in the research and provided necessary ethical approval. All the data received during the research are anonymous and are used only for academic purposes.

3.3. The classroom action research aims were to find out if the use of multifunctional tasks:

- enriches the learner's repertoire of key higher-order thinking skills that he/she demonstrates in the final problem-solving product presented in a foreign language;

- enhances the quality of foreign language communicative competence;

- facilitates the personal learner involvement in text production as an agent.

3.4. Research population and sample

3.4.1. Students

The target student participants of the project were students in language and non-language pre-service teacher education who studied for a bachelor's degree to become subject teachers [foreign languages, biology, history). On the whole, there were 81 students involved. The target student participants were first-year students in non-language pre-service teacher education (future subject teachers) and first- and third-year students of language pre-service teacher education (future English language teachers). The consolidated characteristics of the students who participated in the study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Students' Characteristics

| Non-language students | First-year language students | Third-year language students | |

| Age | 17–19 | 17–19 | 19–21 |

| Number of participants | 34 students | 23 students | 24 students |

| Previous language experience | No language exams were taken on school graduation | General state exam in English as school graduation and a University entrance exam | General state exam in English as school graduation and a University entrance exam |

| Frequency of foreign language classes | Once a week (90 min) | Two times a week (180 min) of conversation classes. Students also have grammar and home reading classes | Two times a week of conversation classes (180 min.). Students also have grammar, and home reading classes |

| Level of language proficiency | A1–A2 | B1–B2 | B2–C1 |

Although there were three groups of students participating in the study, while describing the results, we divided them into two groups (language and non-language) students. Non-language students are quite different from language students in numerous aspects so we decided to look at their results separately.

3.4.2. Teachers

Two teachers of the English Language Department of the Petrozavodsk State University participated in the action research work. Their teaching experiences were 16 and 40 years respectively.

3.5. Materials

Let us look into how multifunctional tasks were designed for the study (see Table 2). They begin with a general assignment presenting the purpose and the expected outcome of the whole task. Then follow sub-tasks specifying which steps exactly students need to take to complete the whole task. Each multifunctional task contains the following student activities:

a) reception (reading, listening or both) aimed at obtaining information;

b) production (speaking and writing) aimed at sharing information;

c) cognitive and metacognitive activities (thinking skills and activity outlining skills) aimed at analyzing and synthesizing information as well as generating ideas;

d) evaluating ideas and generating one's well-grounded points of view;

e) student interaction aimed at exchanging information and opinions, articulating and discussing ideas and views.

Occasionally, there can be language-focused steps preceding those which are more content-focused and more challenging ones. All these activities (steps) are based on the same topic or situation and require the use of approximately similar vocabulary. Their completion suggests activating higher-order thinking skills applied to the same problem/content. They all contribute to achieving the primary goal of the task. The steps can be sequenced in varied ways and they can be backed up with different prompts for those who need scaffolding.

Table 2

Examples of the Tasks in the Study

| Conventional tasks based on PPP model offered to students during the first part

|

Multifunctional tasks offered to students during the second part

|

insert prepositions / give derivatives / do multiple-choice exercises /open the brackets;

|

2. To shape and articulate your opinion on the topic in an essay, do the following assignments:

|

Every class in Part 2 of the study included a multifunctional task elaborated in line with the specific goals and content.

In the final phase of each part, all the students were given a summative problem-solving task (a project) in the context of the topic under discussion which was aimed at revealing their progress in developing both foreign language skills and general/key competences. The participants were expected to express their points of view, provide their arguments, and prove their conclusion, using the ideas and resources of their choice. Thus, the emphasis was placed on the assessment of the students` key competences development rather than solely their language skills and competences. The chain of activities within a multifunctional task can be easily modified, for instance, some of the steps can be done as homework aimed at recycling the materials of the previous class and preparing for the next one. Building up student's individual learning paths also contributes to the development of key competences. Students are offered to use the algorithm borrowed from the task to organize further individual work.

3.6. Assessment Criteria of the Research

To analyze the student integral outcomes that are evident in their final utterances produced in the foreign language (project presentation), the following assessment criteria were used:

1. The originality of the chosen project topic:

- Using one of the sub-topics which have been discussed in the classroom (low level).

- Interpretation of the previously discussed sub-topic with some variations (medium level).

- A new project sub-topic (high level).

2. Reasoning (the number of explicit arguments in the student foreign language presentation):

- 2 explicitarguments (lowlevel).

- 3–4 explicitarguments (mediumlevel).

- A new project sub-topic (high level).

3. The range of mental operations displayed in the student foreign language text:

- 4–5 mental operations explicitly expressed in the presentation(comparison, «for» and «against», superficial conclusion) – low level

- 6–8 mental operations explicitly expressed in the presentation(comparison, samples of «for» and «against», cause and effect, conclusion) – medium level

- More than 9 mental operations explicitly expressed in the presentation(comparison, grouping, samples of «for» and «against», references to personal experience, cause and effect, well-grounded conclusions).

4. Clear and sound personal value judgments expressed in the student foreign language text:

- Superficialpersonal value judgments: like / dislike or agree / disagree (low level).

- Personal judgments are provided but not clearly expressed or grounded (2–3 reasons) (medium level).

- Clear and sound personal value judgments which are well-grounded (high level).

5. Criteria for Foreign Language Communicative Competence are different for non-language and foreign language students considering the difference in the aims and conditions of their university foreign language education. To evaluate the quality of the foreign language communicative competence, we integrated the four modes of communication described in the CEFR (2018): reception, production, interaction, and mediation. We applied a few «can do» descriptors to:

Spoken Production: can deliver appropriate information in an extended text (monologue) addressing listeners.

Listening Comprehension (Reception): can understand oral presentations as well as interaction among other people, being a member of the audience.

Spoken interaction: can give appropriate reactions to the content of the presentation and listener's reactions (ask additional questions, comment, express agreement or disagreement, and evaluate).

Thus, the basic criteria for evaluating the students` foreign language communicative competence were the following:

- Can use a variety of language (both lexical and grammatical) to express mental operations, arguments, and personal judgments.

- Can express content observing language norms and rules (absence of language errors distorting the meaning of the speaker).

- Can participate in spoken interaction using varied ways of addressing partners, stimulating them to develop discourse, and reacting to their utterances. Appropriate reactions also reveal the ability to understand the previous speech of the participants.

Table 3

Description of the Levels of Foreign Language Communicative Competence

of Non-language Students and Language Students

| Levels of Foreign Language Communicative Competence |

Summative Characteristics of Foreign Language Utterances of Non-language Students |

Summative Characteristics of Foreign Language Utterances of Language Students |

| Low Level | Limited vocabulary, repetition of the same words and sentence structures; more than 7 language errors distorting the meaning; 3–4 ways of expressing mental operations, arguments and personal judgments; 3–4 ways of giving appropriate reactions to the content of the presentation and listener's reactions | Limited vocabulary, repetition of the same words and sentence structures; more than 7 language errors; 4–6 ways of expressing mental operations, arguments, and personal judgments; 4–6 ways of giving appropriate reactions to the content of the presentation and listener's reactions |

| Medium Level

|

Varied vocabulary and sentence structures, more than 5–6 language errors distorting the meaning; occasional pauses; 5–6 ways of expressing mental operations, arguments, and personal judgments; 5–6 ways of giving appropriate reactions to the content of the presentation and listener's reactions | Varied vocabulary and sentence structures, more than 5–6 language errors distorting the meaning; occasional pauses; 7–8 ways of expressing mental operations, arguments, and personal judgments; 7–8 ways of giving appropriate reactions to the content of the presentation and listener's reactions |

| High Level

|

Extensive vocabulary and sentence structures, not more than 2–3 language errors, not distorting the meaning; no pauses; 7–8 ways of expressing mental operations, arguments, and personal judgments; more than 7 ways of giving appropriate reactions to the content of the presentation and listener's reactions. ability to achieve the communicative aim successfully | Extensive vocabulary and sentence structures, not more than 2–3 language errors, not distorting the meaning; no pauses; more than 8 ways of expressing a great range of well-grounded ideas, authentic emotions, and personal judgments; more than 8 ways of giving appropriate reactions to the content of the presentation and listener's reactions; ability to achieve the communicative aim successfully |

4. Research Results

The detailed results of both final projects after the use of conventional tasks and the final projects after the use of multifunctional tasks for non-language (Table 2) and language (Table 3) students are presented in the tables below.

Table 4

Results of Non-language Students After the PPP Model

and After the Use of Multifunctional Tasks Shown in Student Percentages

| Conventionaltasks (PPP) model | Multifunctionaltasksmodel | |||||

| low | medium | high | low | medium | high | |

| Originality | 65 % | 24 % | 11 % | 24 % | 59 % | 17 % |

| Reasoning (number of explicit arguments) | 79 % | 18 % | 3 % | 30 % | 59 % | 11 % |

| The range of mental operations | 94 % | 3 % | 3 % | 41 % | 41 % | 18 % |

| Clear and sound personal value judgments | 89 % | 8 % | 3 % | 30 % | 59 % | 11 % |

| Foreign Language Communicative Competence | 44 % | 41 % | 15 % | 32 % | 50 % | 18 % |

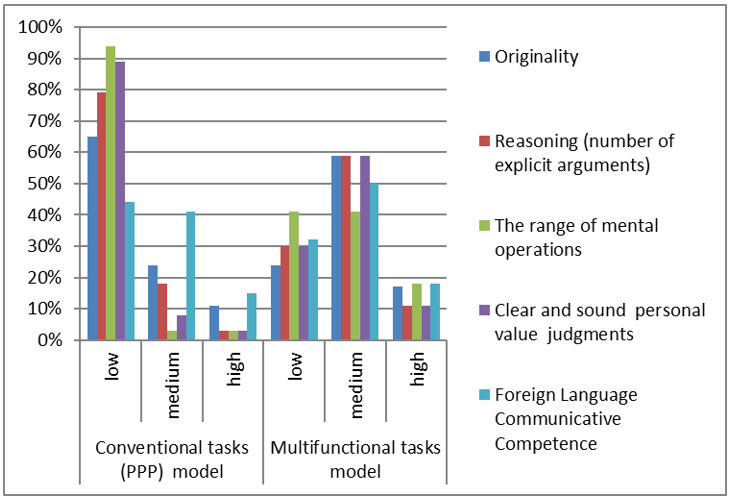

We can also display the shift in the low, the medium, and the high non-language students' foreign language proficiency levels in the bar charts. (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Non-language students' foreign language proficiency levels

The use of the multifunctional task model led to the shift in the number of Non-language students with a low, medium, and high level of key and subject-specific competences. The number of students showing a low level of competence decreased by 40–50 % on the key competence-based criteria and by 12 % on the Foreign Language Communicative Competence criterion. 40–50 % of students who displayed a low level of these competences improved it and reached a medium level. The majority of students which account for 40–59 % reached a medium level of the key competences. The number of students who displayed a high level of the key competences increased dramatically from 3 to 18 %. The Foreign Language Communicative Competence did not change so significantly.

Table 5

Results of Language Students after the PPP Model and after the Use

of Multifunctional Tasks Shown in Student Percentages

| Conventionaltasks | Multifunctionaltasksmodel | |||||

| low | medium | high | low | medium | high | |

| Originality | 64 % | 21 % | 15 % | 15 % | 60 % | 25 % |

| Reasoning (number of explicit arguments) | 45 % | 45 % | 10 % | 17 % | 60 % | 23 % |

| The range of mental operations | 85 % | 10 % | 5 % | 17 % | 55 % | 28 % |

| Clear and sound personal value judgments | 38 % | 43 % | 19 % | 12 % | 21 % | 67 % |

| Foreign Language Communicative Competence | 26 % | 38 % | 36 % | 19 % | 42 % | 40 % |

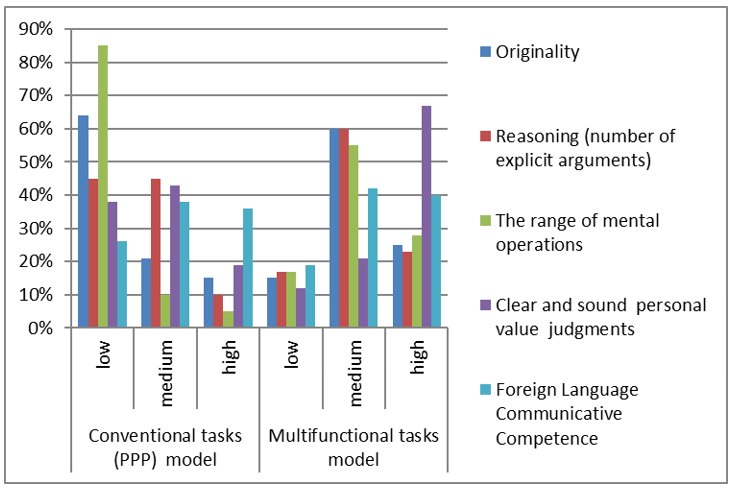

We can also display the shift in the low, the medium, and the high language students' foreign language proficiency levels in the bar charts (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The language students' foreign language proficiency levels

The results of language students are quite similar to the results of non-language students with slight variations. In the conventional task-based model the majority of students displayed a low level on key competences-based criteria. Their results are comparable to the results of non-language students and the trend is the same. However, there is a specific feature as the Foreign Language Communicative Competence is developed much better in language students, the overall majority of language students (74 %) displayed a medium or high level of the subject-specific language competence (38 % and 36 % respectively). We can see the same shift in the number of students with a low, medium, and high level of proficiency after the use of the multifunctional task-based model. The proportion of students with a low level of key competences decreased significantly by approximately 40–50 % on the key competences-based criteria and it showed a slight decrease on the subject-specific competence. The use of multifunctional tasks resulted in the majority of students reaching a medium level of originality (60 %), reasoning (60 %), and the range of mental operations (55 %) or a high level of clear and sound personal judgment (67 %). The chunk of students who showed a high level of the key competences increased substantially. However, the proportion of students with a low, medium and high level of the Foreign Language Communicative Competence remained almost the same.

The shift in the number of students with a low level of the foreign language competence was proved statistically through the Chi-square test. The results of the test on each criterion are presented in the following tables.

Table 6

Results of the Chi-square Statistic on Originality

of the Chosen Topic Criterion for Non-language Students

| Results | |||

| Conventional tasks | Multifunctional tasks | Row Totals | |

| Number of non-language students with a low level of foreign language competence | 22 (15.00) [3.27] | 8 (15.00) [3.27] | 30 |

| Number of non-language students with a medium level of foreign language competence | 8 (14.00) [2.57] | 20 (14.00) [2.57] | 28 |

| Number of non-language students with a high level of foreign language competence | 4 (5.00) [0.20] | 6 (5.00) [0.20] | 10 |

| Column Totals | 34 | 34 | 68 (Grand Total) |

The Chi-square statistic is 12.0762. The p-value is 0.002386. The result is significant at p < 0.05.

Table 7

Results of the Chi-square Statistic on Originality

of the Chosen Topic Criterion for Language Students

| Results | |||

| Conventional tasks | Multifunctional tasks | Row

Totals |

|

| Number of language students with a low level of foreign language competence | 30 (18.50) [7.15] | 7 (18.50) [7.15] | 37 |

| Number of language students with a medium level of foreign language competence | 10 (19.00) [4.26] | 28 (19.00) [4.26] | 38 |

| Number of language students with a high level of foreign language competence | 7 (9.50) [0.66] | 12 (9.50) [0.66] | 19 |

| Column Totals | 47 | 47 | 94 (Grand Total) |

The Chi-square statistic is 24.1394. The p-value is < 0.00001. The result is significant at p < 0.05.

The Chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relation between the use of multifunctional tasks and the number of students with the low, medium, and high level of the project topic originality. The relation between these variables was significant, multifunctional tasks appeared more effective than conventional tasks in developing the students` foreign language competence. We can conclude that multifunctional tasks stimulate the students` creativity and originality, learners become more confident in the use of foreign language and are more likely to develop original topics for their projects.

Table 8

Results of the Chi-square Statistic on Reasoning (number of explicit arguments) Criterion for Non-language Students

| Results | |||

| Conventional tasks | Multifunctional tasks | Row

Totals |

|

| Number of non-language students with a low level of foreign language competence | 27 (18.50) [3.91] | 10 (18.50) [3.91] | 37 |

| Number of non-language students with a medium level of foreign language competence | 6 (13.00) [3.77] | 20 (13.00) [3.77] | 26 |

| Number of non-language students with a high level of foreign language competence | 1 (2.50) [0.90] | 4 (2.50) [0.90] | 5 |

| ColumnTotals | 34 | 34 | 68 (Grand Total) |

The Chi-square statistic is 17.1493. The p-value is 0.000189. The result is significant at p < 0.05.

Table 9

Results of Chi-square Statistic on Reasoning (number of explicit arguments) Criterion for Language Students

| Results | |||

| Conventional tasks | Multifunctional tasks | Row

Totals |

|

| Number of language students with a low level of foreign language competence | 21 (14.50) [2.91] | 8 (14.50) [2.91] | 29 |

| Number of language students with a medium level of foreign language competence | 21 (24.50) [0.50] | 28 (24.50) [0.50] | 49 |

| Number of language students with a high level of foreign language competence | 5 (8.00) [1.12] | 11 (8.00) [1.12] | 16 |

| ColumnTotals | 47 | 47 | 94 (Grand Total) |

The Chi-square statistic is 9.0776. The p-value is 0.010686. The result is significant at p < 0.05.

The relation between these variables was significant. Multifunctional tasks are more effective than conventional tasks in developing the students` ability to clearly express a greater variety of arguments in a foreign language. As multifunctional tasks stimulate and outline student reasoning, they produce a wider range of explicit arguments.

Table 10

Results of the Chi-square Statistic on the Range

of Mental Operations Criterion for Non-language Students

| Results | |||

| Conventional tasks | Multifunctional tasks | Row

Totals |

|

| Number of non-language students with a low level of foreign language competence | 32 (23.00) [3.52] | 14 (23.00) [3.52] | 46 |

| Number of non-language students with a medium level of foreign language competence | 1 (7.50) [5.63] | 14 (7.50) [5.63] | 15 |

| Number of non-language students with a high level of foreign language competence | 1 (3.50) [1.79] | 6 (3.50) [1.79] | 7 |

| Column Totals | 34 | 34 | 68 (Grand

Total) |

The Chi-square statistic is 21.8816. The p-value is 0.000018. The result is significant at p < 0.05.

Table 11

Results of the Chi-square Statistic on the Range

of Mental Operations Criterion for Language Students

| Results | |||

| Conventional tasks | Multifunctional tasks | Row

Totals |

|

| Number of language students with a low level of foreign language competence | 40 (24.00) [10.67] | 8 (24.00) [10.67] | 48 |

| Number of language students with a medium level of foreign language competence | 5 (15.50) [7.11] | 26 (15.50) [7.11] | 31 |

| Number of language students with a high level of foreign language competence | 2 (7.50) [4.03] | 13 (7.50) [4.03] | 15 |

| Column Totals | 47 | 47 | 94 (Grand Total) |

The Chi-square statistic is 43.6258. The p-value is < 0.00001. The result is significant at p < 0.05.

The Chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relation between the use of multifunctional tasks and the number of students with low, medium, and high ranges of mental operations. The relation between these variables was significant, multifunctional tasks are more effective than conventional tasks in widening the students' mental operations range.

The use of multifunctional tasks entails the students' intellectual engagement. They focus on performing varied thinking operations expressing the outcomes in the foreign language. It leads to an increase in the range of mental operations involved in the production of their texts.

Table 12

Results of the Chi-square Statistic on Clear and Sound Personal Value

Judgments Criterion for Non-language Students

| Results | |||

| Conventional tasks | Multifunctional tasks | Row

Totals |

|

| Number of non-language students with a low level of foreign language competence | 30 (20.00) [5.00] | 10 (20.00) [5.00] | 40 |

| Number of non-language students with a medium level of foreign language competence | 3 (11.50) [6.28] | 20 (11.50) [6.28] | 23 |

| Number of non-language students with a high level of foreign language competence | 1 (2.50) [0.90] | 4 (2.50) [0.90] | 5 |

| Column Totals | 34 | 34 | 68 (Grand Total) |

The Chi-square statistic is 24.3652. The p-value is < 0.00001. The result is significant at p < 0.05.

Table 13

Results of the Chi-square Statistic on Clear

and Sound Personal Value Judgments Criterion for Language Students

| Results | |||

| Conventional tasks | Multifunctional tasks | Row Totals | |

| Number of language students with a low level of foreign language competence | 18 (12.00) [3.00] | 6 (12.00) [3.00] | 24 |

| Number of language students with a medium level of foreign language competence | 20 (15.00) [1.67] | 10 (15.00) [1.67] | 30 |

| Number of language students with a high level of foreign language competence | 9 (20.00) [6.05] | 31 (20.00) [6.05] | 40 |

| ColumnTotals | 47 | 47 | 94 (Grand Total) |

The Chi-square statistic is 21.4333. The p-value is 0.000022. The result is significant at p < 0.05.

The relation between these variables is significant, multifunctional tasks are more effective than conventional tasks in developing the students` ability to regularly shape and express their attitude to the problem under discussion in the foreign language. Both the non-language and language students tend to express their personal opinions more explicitly and provide better grounded, clear, and sound personal value judgments after performing multifunctional tasks.

Table 14

Results of the Chi-square Statistic on Foreign Language Communicative

Competence Criterion for Non- language Students

| Results | |||

| Conventional tasks | Multifunctional tasks | Row Totals | |

| Number of non-language students with a low level of foreign language competence | 15 (13.00) [0.31] | 11 (13.00) [0.31] | 26 |

| Number of non-language students with a medium level of foreign language competence | 14 (15.50) [0.15] | 17 (15.50) [0.15] | 31 |

| Number of non-language students with a high level of foreign language competence | 5 (5.50) [0.05] | 6 (5.50) [0.05] | 11 |

| Column Totals | 34 | 34 | 68 (Grand Total) |

The Chi-square statistic is 0.9966. The p-value is 0.607558. The result is not significant at p < 0.05.

Table 15

Results of the Chi-square Statistic on Foreign Language Communicative

Competence Criterion for Language Students

| Results | |||

| Conventional tasks | Multifunctional tasks | Row

Totals |

|

| Number of language students with a low level of foreign language competence | 12 (10.50) [0.21] | 9 (10.50) [0.21] | 21 |

| Number of language students with a medium level of foreign language competence | 18 (19.00) [0.05] | 20 (19.00) [0.05] | 38 |

| Number of language students with a high level of foreign language competence | 17 (17.50) [0.01] | 18 (17.50) [0.01] | 35 |

| Column Totals | 47 | 47 | 94 (Grand Total) |

The Chi-square statistic is 0.5624. The p-value is 0.754875. The result is not significant at p < 0.05.

5. Discussion

In the present research, the comparison of conventional and multifunctional tasks shows that the second way of organizing the education process demands more structuring, instruction, and more diverse materials. The multifunctional task strategy provides students with clear steps on the way to their final aim in each task. They become more aware of what should be done to achieve the goal of the whole task. Each step shifts their focus to a specific aspect, all of them together contributing to the quality of the final product. During the performance of the final task on the topic, when students have to complete some problem-solving assignment on their own, without any prescribed sequence of steps, they demonstrate more independence in the choice of the problem, in structuring the content, in the variety of cognitive and metacognitive strategies and use of the language.

As we can see, the relation between these variables is not significant, so we cannot conclude that multifunctional tasks contribute to the development of foreign language communicative competence significantly more than conventional tasks. Both strategies are effective while developing foreign language communicative competence. However, from the previous results, we can see that multifunctional tasks stimulate both non-language and language students to be more independent thinkers, to produce more original and creative topics for their projects, to express their ideas more explicitly, to provide better argumentation for their opinion, and to use a wider range of mental operations in their texts to express a well-grounded personal opinion. These are essential key competencies, vital for any sphere of professional and personal life. Thus, we can conclude that both multifunctional tasks and conventional tasks develop foreign language communicative competence. Meanwhile, the first type is much more effective in developing students' key competencies transferrable to other areas of human activities. One more essential advantage of multifunctional tasks is that they contribute to the development of the students` key competencies regardless of the level of their foreign language communicative competence. The study has proved that A1–A2-level students as well as higher-level students equally benefit from multifunctional tasks in university foreign language education.

There is an evident increase in the student agency in varied activities and the level of their independence. They display initiative and growing confidence in choosing the topic and develop readiness and awareness of how to do complex, challenging tasks in the foreign language, demonstrating critical and logical thinking strategies. Students develop readiness and ability to cooperate with others in the foreign language to achieve results. Their collaboration in the course of interaction reveals their respectful attitude towards other people's ideas and opinions. All the students are ready to express their personal opinions and attitudes to the issue under discussion, providing at least a few arguments to support their message The foreign language fluency of the student discourse noticeably improves, though the accuracy in the use of the foreign language needs further practice.

The action research has proved the benefits of multifunctional tasks in achieving integral goals of foreign language education for both language and non-language university students.

6. Conclusion

In line with modern education standards requirements, the educational input is supposed to result in students` acquiring new competencies which can be both quite narrow (referring, for instance, to an academic course) as well as quite wide (key/general competences referring to any sphere of human activity), and simultaneously developing students` values, norms of behavior or personality traits.

As the study proved, one of the effective tools in this direction is multifunctional tasks that are designed so that they result in integral outcomes (subject-specific, general, personal, and professional) as a personal asset. Unlike mono-functional tasks and exercises aimed at practising one specific language skill or sub-skill, multifunctional tasks promote the achievement of several integral aims which cumulatively bring about the evolvement of a unique, creative, and active personality.

A significant advantage of this kind of tasks is that they can be applied and integrated into any topic, regardless of the learners' foreign language communicative competence level, they can be adapted for various fields, and contexts of education which makes them a universal tool to achieve modern education aims. Contributing to the development of students' agency, multifunctional tasks provide input into their future as responsible, independent, and active specialists, able to collaborate and communicate, think critically and express well-grounded opinions while solving problems in their diverse activities.

7. Limitation and Study Forward

The study compared only two models: a conventional task-based (PPP) model and a multifunctional task-based model while a variety of models are used by teachers in the classroom. Additionally, the research population was limited by university students and teachers, so the conclusions cannot be generalized to other categories of learners. Therefore, a further study involving other learning models and other learners should be conducted.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization, E. B. and M. S.; Methodology, E. B.; Investigation, M. S.; Data Curation, E. B., and M. S.; Validation, M. S.; Formal Analysis, E. B.; Writing – original draft preparation, E. B. and M. S.; Software, M. S.; Visualization, M. S.; Writing – review and editing, E. B. and M. S.

References

- Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. [Electronic resource]. Council of Europe, 2001. Electron dan. URL: https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages (date of acсess 04.01.2021).

- Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment Companion Volume with New Descriptors [Electronic resource]. Council of Europe; 2018. Electron dan. URL: www.coe.int/lang-cefr (date of acсess 04.01.2021).

- Russian Education Standards for General Education [Electronic resource]. 2015. Electron dan. http://docs.cntd.ru/document/902254916 (date of acсess 14.01.2021). (In Russ.)

- Federal State Higher Education Standards 3++. 2018 [Electronic resource]. Electron dan. http://fgosvo.ru/fgosvo/151/150/24 (date of acсess 14.01.2021). (In Russ.)

- Almazova N. I., Baranova T. A., Khalyapina L. P. Pedagogical approaches and CLIL in foreign and Russian language education [Electronic resource]. In: Yazyk i kul'tura. 2017. № 39. P. 116–134. (In Russ.)

- Borzova E. V. Diversity of Materials and Tasks as an Incentive for Strudent Interaction in the Foreign Language Classroom. In: Inostrannye yazyki v shkole. 2017. № 9. P. 11–17.

- Kitaigorodskaya G. A. Metodological foundations of intensive teaching foreign languages // In: Inostrannyi yazyk v shkole. 1988. № 6. P. 15. (In Russ.)

- Passov E. I. Forty years later or one hundred and one teaching idea. Moskow : Glossa-Press, 2006. 240 p. (In Russ.)

- Solovova E. N. Foreign language teaching. Basic course. Moskow, 2002. 239 p. (In Russ.)

- Baralt M., Gilabert R., Robinson P. Task Sequencing and Instructed Second Language Learning, London : Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

- Coulson D. Collaborative Tasks for Cross-cultural Communication in Teachers Exploring Tasks in English Language Teaching. S. l., 2005, P. 127–138.

- Cukier W., Hodson J., Omar A. «Soft» Skills Are Hard. A Review of the Literature. Ryerson University, Diversity Institute. Canada, 2015.

- Davies M. Concept mapping, mind mapping and argument mapping: What are the differences and do they matter? In: Higher Education. 2011. № 62 (3). P. 279–301.

- Fortanet-Gomez I. and Raisanen C. A. (Eds.) European Commission: Language teaching: Integrating Language and Content. S. l., 2008.

- Greenberg D. A., Nilssen H. Andrew. The Role of Education in Building Soft Skills Putting into Perspective the Priorities and Opportunities for Teaching Collaboration and Other Soft Skills in Education. S. l., 2015. 32 p.

- Leontiev A. A. Beyond barriers: Language, culture, personality, activity. In: Journal of Russian and East European Psychology. 2006. № 44 (3).

- Leontiev A. A. Psychology and the Language Learning Process. Oxford : Pergamon, 1981. P. 21–28.

- Li R. F. Foreign Language Teaching and the Cultivation of Students' Creativity and Critical Thinking. In: Foreign Language Education. 2002. № (23). P. 61–64.

- Liu R. Q. Cultivation of Critical Thinkingin Foreign Language Teaching. In: China Adult Education. 2015. P. 134–135.

- McNamara T. Language and Subjectivity. In: Language and Subjectivity (Key Topics in Applied Linguistics, p. I). Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Nunan D. Classroom research. In: Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning. Mahwah, NJ : Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2005. P. 225–240.

- Parupalli S. R. The Need to Develop Soft Skills Among The English language Learners in the 21st Century. In: Research Journal Of English (RJOE). 2019. № 4 (2), P. 286–292.

- Sun B. H., Zhang, X. Y. Critical Thinking Teaching Model and Its Reference and Enlightenment to Foreign Language Teaching Reform. In: Journal of Shanxi Youth Vocational College. 2018. (31): P. 110–112.

- Weaver C. Willingness to Communicate: A Mediating Factor in the Interaction between Learners and Tasks in Tasks in Action: Task-Based Language Education from a Classroom-Based Perspective. Cambridge Scholars Publishing 15 Angerton Gardens. Newcastle, 2007. P. 159–193.

- Willis D., Willis J. Doing Task-based Teaching. Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Zhang X. Q. On the Construction of Critical Thinking in Foreign Language Teaching. In: Education and Vocation. 2009. № (32). P. 95–97.

- Borzova E., Shemanaeva M. A University Foreign Language Curriculum for Pre-Service Non-Language Subject Teacher Education [Electronic resource]. In: Educ. Sci. 2019. № 9. P. 163. Electron dan. URL: https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9030163 (date of acсess 14.01.2021).

- Brown V. R., Paulus P. B. Making Group Brainstorming More Effective: Recommendations from an Associative Memory Perspective. [Electronic resource]. In: Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2002. № 11 (6). P. 208–212. Electron dan. DOI:10.1111/1467-8721.00202 (date of acсess 14.01.2021).

- Bula-Villalobos O., Murillo-Miranda C. Task-based Language Teaching: Definition, Characteristics, Purpose and Scope [Electronic resource]. In: International Journal of English, Literature and Social Sciences (IJELS). 2019. № 4 (6). Electron dan. URL: https://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijels.46.39 (date of acсess 14.01.2021).

- Cordoba E. Implementing task-based language teaching to integrate language skills in an EFL program at a Colombian University. Revista PROFILE [Electronic resource]. In: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development. 2016. № 18 (2). P. 13–27. Electron dan. URL: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n2.49754 (date of acсess 14.01.2021).

- Deming D. J. The Value of Soft Skills in the Labor Market. [Electronic resource]. In: NBER Reporter, 2017. № 4. Electron dan. URL: https://www.nber.org/reporter/2017number4/deming.html (date of acсess 14.01.2021).

- Ferguson S. Same task, different paths: Catering for student diversity in the mathematics classroom. [Electronic resource]. In: APMC 2009. № 14 (2) The 14th Asia Pacific Management Conference Enhancing Sustainability in the Asia Pacific: Entrepreneurship and Innovation the Airlangga University, Indonesia, in collaboration with the National Cheng Kung. Electron dan. URL: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ853838.pdf (date of acсess 24.01.2021).

- Kansızoğlu H. The Effect of Graphic Organizers on Language Teaching and Learning Areas: A Meta-Analysis Study. [Electronic resource]. In: TED EĞİTİM VE BİLİM. S. l., 2017. Electron dan. DOI: 42. 10.15390/EB.2017.6777 (date of acсess 14.01.2021).

- Kic-Drgas J. Development of soft skills as a part of an LSP course [Electronic resource]. In: E-mentor. 2018. 2/74. Electron dan. URL: http://www.e-mentor.edu.pl/mobi/artykul/index/numer/74/id/1349 (date of acсess 14.01.2021).

- Larsen-Freeman D. On language learner agency: A complex dynamic systems theory perspective [Electronic resource]. In: The Modern Language Journal. 2019. № 103 (S1). P. 61–79. Electron dan. URL: https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12536 (date of acсess 14.01.2021).

- Levina L., Lukmanova O., Romanovskaya L. & Shutova T. Teaching Tolerance in the English Language Classroom [Electronic resource]. In: Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2016. № 236. P. 277–282. Electron dan. DOI: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.12.029 (date of acсess 14.01.2021).

- Matukhin D. L., Gorkaltseva E. N. Teaching Foreign Language for Specific Purposes in Terms of Professional Competency Development [Electronic resource]. In: Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy. 2015. Vol 6. № 1. January. Electron dan. URL: https://www.e-education.psu.edu/eme807/node/698 (date of acсess 14.01.2021).

- Nurdan A. The role of English as a foreign language classes in tolerance education in relation to school management practices [Electronic resource]. In: Quality & Quantity: International Journal of Methodology. 2018. Vol. 52 (2). P. 1167–1177. Electron dan. DOI: 10.1007/s11135-017-0575-7 (date of acсess 14.01.2021).

- Tevdovska E. Integrating Soft Skills in Higher Education and the EFL Classroom: knowledge beyond language learning [Electronic resource]. In: SEEU Review (South East European University). 2015. № 11 (2). P. 97–108. Electron dan. URL: https://doi.org/10.1515/seeur-2015-0031 (date of acсess 14.01.2021).

- The Definition and Selection of Key Competencies. Executive Summary. The DeSeCo Project. 2005 [Electronic resource]. Electron dan. URL: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/35070367.pdf (date of acсess 25.01.2021).

- Tikhonova E., Raitskaya, L., Solovova, E. Developing Soft Skills in English for Special Purposes Courses: The Case of Russian Universities [Electronic resource]. In: 5th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Arts SGEM-2018. 2018. № 18. P. 223–232. Electron dan. URL: https://doi.org/10.5593/sgemsocial2018/3.4/s13.028 (date of acсess 14.01.2021).

- Urfa M. Flipped Classroom Model and Practical Suggestions [Electronic resource]. In: Journal of Educational Technology & Online Learning. 2018 № 1 (1). P. 47–59. Electron dan. DOI: 10.31681/jetol.378607 (date of acсess 14.01.2021).