1. Introduction

This study presents a perspective on the legacy of two generations who have shaped (and are still shaping), a scientific legacy for the upcoming generations. As always, every generation has its own peculiarities, but every generation also creates a legacy which influences future generations directly and indirectly.

The term "generation" appears in numerous scientific fields, e.g. biology, culturology, economics, genealogy or sociology, and we can interpret it via the perspective of these fields. Demographic interpretation is also frequently used. Demography understands generation in terms of the reproduction of the human year, and in the Czech Republic, generations are generally divided by 20 years. Therefore, we can identify the generation of children, parents, grandparents, and even great-grandparents. However, this biological conditionality is determined by cultural and social factors, which significantly influence this interval. Nowadays it is clear that many young women do not give birth at the age of twenty. This simple reasoning naturally shifts the term generation elsewhere, and the most appropriate prism seems to be the sociological one. As stated by P. Sak and K. Kolesárová (2012), the frequency of the appearance of demographic generations is more stable, with more or less the same amplitudes. Sociological generations tend to have the amplitudes with lesser or bigger deviations.

The term generation is therefore also a sociological category, whose meaning is relatively well known because of its widespread mainstream use. In this context, the generation is frequently understood as a group of people of similar age. According to J. Scott and G. Marshall (2005), generation is a form of an age group consisting of the members of society born at about the same time.

In this study, we focus on two case studies which were created from interviews with the representatives of two generations. The first is the Silent Generation (born between 1925 and 1945), whose members have been affected by the Second World War and the economic depression, and who are marked by their trusting nature, conformity and loyalty, who appreciate stability, are engaged in civic life and have large families. They are sometimes called “the children of the Great Depression”; they value the traditional family and traditional roles within it, i.e. the man is the breadwinner and makes decisions while the woman cares for the children and household, and together with children has to do what she is told. This generation is characterised by their authoritative approach towards their children and grandchildren. Their conservatism is expressed in their general inclination towards spending their whole working life in one job, and analogously not moving home much. The Generation of Baby Boomers (born between 1946 - 1964, also known as the “happy generation”), were marked by their high birth rate. Typical for this generation is high purchasing power, values, comfort and hedonism as motivation, materialism and idealism, rebellion against the traditional family and the patriarchal authority of fathers, the sexual revolution, and high female employment in the Eastern and Western bloc. The communication revolution had a great influence in shaping the Baby Boomers, in particular the invention of the television. These two generations are strongly represented at Czech universities nowadays, and they play a significant role in expert activities and in assisting younger researchers.

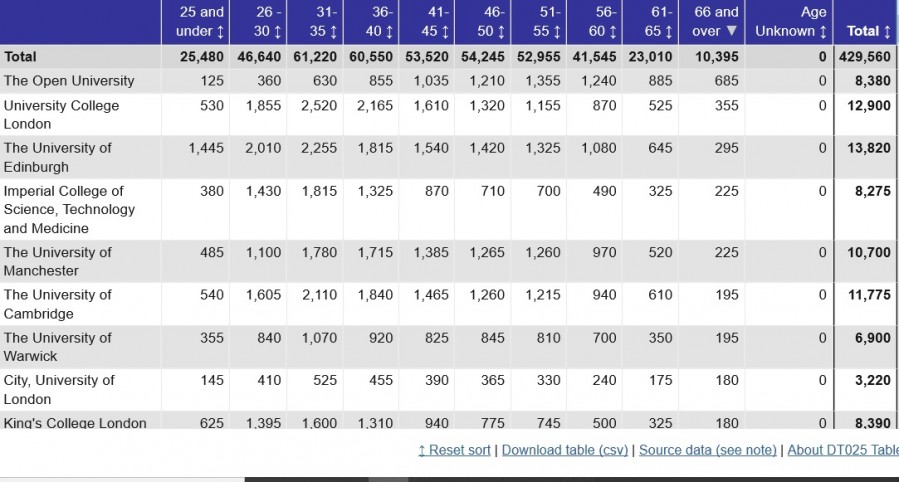

The senior academics are represented at the universities all around the world. For evidence see the Figure 1. They are part of the academic environment and they are a relevant part of the faculty at universities. In the following text we present what their opinions are and what legacy they offer for the present day.

Fig. 1: An overview of universities with senior academics

2. Objectives

The research, whose partial results we are submitting, is aimed at clarifying and revealing the lives of representatives of the two generations who have influenced current events at universities in the Czech Republic. The research also reveals the shaping of their professional careers in the context of their era. The research involves academics who are over 65 years old and are still employed at Czech universities. We include two borderline case studies which do, however, illustrate in great detail the abovementioned generations.

Our first research participant is a woman who has been working at the university for over 40 years. She is one of the leading experts in education theory and holds a professorial position. In terms of age, she comes from the Generation of Baby Boomers and, as she says herself, was “significantly influenced by the Silent Generation.” She “found many friends among them, learnt a lot from them and continues to do so.”

The second participant is a man – a representative of the Silent Generation. He remains one of the leading figures in education theory, he is actively tutoring his Ph.D students, leading and forming research teams, and serves as an example of a model professor and excellent teacher.

The design of this study is qualitative, and is rooted in the tradition of interpretivism. Three methods of data collection were used to acquire complex answers to the research questions: thematic writing, semi-structured interviews, and metaphor creation. The participants wrote thematic writing (Richardson, 1994; Elizabeth, 2007), framed by open questions concerning their views on the research topics. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to clarify some answers produced in thematic writing. Writing and interview transcripts were repeatedly re-read and then processed via systematic open coding. The results of the first stage of the analysis were encoded segments of texts and a list of codes. In the second stage of the analysis, the codes were grouped into semantically unified segments, which were then named. In this way, the themes emerged from thematic writing and from interviews. In the subsequent stage, we tested the relevance of the themes and their appearance in the text segments. Consequently, we provided theoretical interpretation, which, in the case of thematic writing, resulted in an analytical story. The data was essentially analysed in adherence with the principles of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

3. Findings

Common features can be found in both generations.

a) Nothing was available, or methodology was in its infancy

One significant piece of testimony was about how methodology developed in the Czech and Slovak Republic (both states were part of one joint state until the 1990s).

“When we wanted to do research, we had to seek books, contacts and also consider how we were going to collect data. There were no such techniques like there are today. Nothing was available. We learnt to work on our own research methodologically, and we based this primarily on our own experience. Methodology was in its infancy.”

Academic work in the 1970s and 1980s included a desire to find out, which stemmed from the fact that contacts abroad and travelling were impossible. It was a difficult art to get access to a foreign article, as it was to purchase a foreign academic book. There was no book on methodology in the Czech Republic, and most research was based on a quantitative design. When anyone wanted to travel abroad, vetting had to be undertaken, meaning even the academic environment had a political context. There was a lack of academic literature at universities, and the textbooks focused more on explaining the “correct political opinion”. In Czechoslovakia, there were only two books which were part of obligatory reading.

“The first two chapters were on Marxist philosophy; you couldn’t learn anything from that. And so I began to write. After 1989 I was great inspired by foreign textbooks, especially American ones, where there was much competition between authors; so I knew when something was published it was going to be a good publication. When a book was published, it had to be really good not just in terms of content, but also style, teaching aids. So I learnt a lot.”

The testimony demonstrates clear endeavours to collaborate and seek out mutual contacts both domestically and internationally, and to find literature which was different and without traces of Marxism. As in case of young people starting their Ph.D study or university work, both participants expressed a desire for mutual sharing of information and contacts. This is something the generations we are looking at have in common with Generation X and Y. There are differences here, though. For Generations X and Y, the individualist pursuit of their own interests is typical. For the generations we focused on, the focus is more on social impact, and an endeavour that, “others can get involved too, so others can share what I know too.”

b) I need to speak to someone, or science isn’t just about numbers. Above all it is about people

Academic socialisation was different in the 1970s and 1980s. Friendship was highly valued and it also affected one᾽s work. Colleagues helped each other and they depended on each other.

“I got the chance to make friends with some truly great figures. I am grateful for that.”

“I remember our meetings on developing primary education in all departments throughout Czechoslovakia. We liked each other and we were interested in our personal lives, too.”

Each individual belongs to several social groups. Membership in a group substantially affects an individual᾽s self-perception, which is affected by personal constructs. Those, in turn, shape an individual’s self-concept. In an occupational group, an individual compares himself/herself with other individuals, by which the self-concept is moulded and changed.

Adaptation, then, is a process of an individual’s adjustment to the environment, a situation or a group, and is closely connected with the individual᾽s identification with a workplace. The individual identifies with social groups to which they belong, and this identification determines the way they interact with others. This idea was developed by H. Tajfel (1982), who claims that the process of social identification is essential for understanding interpersonal interactions. Tajfel is convinced that human reasoning is based on the process of perception of other people and that it influences other processes, especially the formation of social norms as well as stereotypes and prejudices.

Norms, rules and goals of a group which accepts a new employee are important for occupational processes. These occupational components influence the way a new university teacher will accept their position at the university.

4. Conclusion

Both case studies give strong positions on how the younger generations work, where science is heading and what problems are emerging. Both participants agreed in their opinions on the system of assessing published outputs in the Czech Republic. Both think, “that the system does not nurture researchers, but rather points collectors.” They believe that young academics have “many opportunities to develop”, while they did not. They are not sure whether the young researchers appreciate these opportunities sufficiently.

According to the participants, students, Ph.D students and academics have the following opportunities:

- improving their knowledge of foreign languages,

- travelling,

- acquiring funding through various support grants,

- acquiring any academic literature wanted,

- access to various international databases,

- working with various technologies which facilitate their work.

Both participants clearly declare their effort and desire to work and “be useful to younger colleagues”. They want to help and be in the role of experts able to hand over their experience. Both have experienced major personal changes when they had to leave their original workplaces where they had worked for dozens of years. Both work at smaller regional universities.

“I had to leave my previous workplace. I was 70 years old, so they implied that I no longer belonged there.”

Although biased perception and distortions are often linked to racial and gender discrimination within organisations, the perception of older people within organisations is an area of growing importance. This issue is becoming more serious as the number of older people in the population grows, and also as older people are healthier and fitter compared to people of the same age in the past (Brooks, 2003). Some of the most frequent stereotypes about older people include that they are slow, in poor physical condition, cannot cope with modern technology, find it hard to understand new ideas, cannot adapt to changes well, and learn more slowly.

Such stereotypes can be refuted in their entirety by the participants in our investigation. What represents another advantage for them is the fact that both are extremely loyal and reliable. Both support the young generation. They say that, “clever young people are important for every system,” and they are the bearers of positive changes. However, they also state that the career of those born earlier is not finished either. They want to continue to give. Their identity is linked to the academic environment in which they would like to continue to operate, and in which they would like to experience future success.

The career construction theory of D. E. Super (1996, quoted by Savickas, 2002) shows a link between self-concept and a professional career. Super maintains that people differ in their abilities, personalities, needs, values, interests, traits, and self-concepts. Therefore, they are naturally qualified for a number of occupations. Each occupation requires a characteristic pattern of abilities and personality traits. The nature of a career is determined by an individual’s socioeconomic status, mental ability, education, skills, personality characteristics, career maturity, and by the opportunities to which one is exposed. In the professional career, an individual decides how to manage the transition from one phase to another, the success of which depends on the readiness of an individual to cope with the demands of that phase. Career development is essentially implementing occupational self-concepts. Career decisions reflect one᾽s attempts at translating one᾽s self-understanding into career terms (Super, 1984). Self-concepts develop over time, making career choices and adjusting to them is a lifelong task.

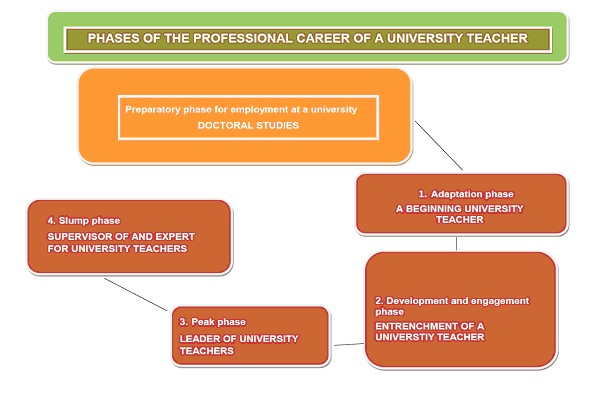

After describing the concepts of personal value, personal construct, self-concept and self-efficacy, a model of the career phases of a university teacher will be introduced. The model comprises five career phases, spanning from the preparatory phase to the slump phase. None of these phases can be circumscribed by time, age or the academic degrees of a university teacher.

Fig. 1 Phases of the professional career of a university teacher – ideal model (Wiegerová, 2016)

- The adaptation phase. In the university environment, the beginner is a newcomer to the institution, s/he explores different activities and roles and adjusts preferences, interests and abilities. Gradually, the individual identifies with the workplace. This phase is not easy to delineate because there are large inter-individual differences. It is as individual-specific as is self-concept, which an individual begins to create, based on social comparison. If personal construct collides with a workplace reality, and it cannot be changed, an individual leaves the workplace.

- The development and engagement phase. In this phase, a university teacher becomes a fully-fledged employee, with a developed teacher identity. The employee is an independent staff member and may hold certain posts in the organization᾽s hierarchy. In addition to teaching responsibilities, the employee is expected to conduct research projects and publish. This phase suggests how a university teacher᾽s self-concept will be shaped in the future, which factors will affect it, and how the rules of social comparison will be set.

- The peak phase. A university teacher becomes an important staff member who contributes to the university᾽s success. Universities engage these experienced teachers in a variety of advising and supervising tasks. They are expected to actively engage in managing the careers of their younger colleagues. However, some university teachers might feel their occupational aspirations are not fulfilled and may leave the university.

- The slump phase. In this phase, the influence and attainments of a teacher decline in the organization. However, universities retain them as an important individual who shapes the university career.

The model we submit represents the ideal view of how universities should work, where experienced academic workers should hold an important role. The research we have outlined to readers is just the beginning. As such, we have presented just a short section of it. The research will continue in a qualitative design in gratitude to all university teachers who began to develop it in the former Czechoslovakia at the beginning of the 1980s.

References

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101.

- Brooks, I. (2003). Firemní kultura. Praha: Computer Press.

- Elizabeth, V. (2007). Another string to our bow: Participant writing as research method. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(1), Art. 31. Retrieved Dec. 1, 2013,from http://www.qualitativeresearch.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/331/723

- Richardson, L. (1994). Writing as a method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 516–528). London: Sage.

- Sak, P., & Kolesárová, K. (2012). Sociologie stáří a seniorů. Praha: Grada.

- Scott, J., & Marshall, G. (2005). Oxford Dictionary of Sociology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Super, D. E., Super, C., & Savickas, M.L. (1996). A life-span, life-space approach to careers. Career Choices and Developments, 3, 212-178.

- Tajfel, H. (1982). Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology, 33(1), 1-39.

- Wiegerová, A. (2016) The careers of young Czech University teachers in the Field of Pedagogy. Zlín: Tomas Bata University in Zlín.