1. Introduction

Foster care is an increasingly popular type of substitute family care in the Czech Republic1. It is based on the considerable similarity of foster care with ordinary family care. Like family care, foster care also offers long-term and regular (daily) contact with persons representing parents in the normal living environment (flat, house). In this way, foster care enables the child to establish a deep and strong relationship with the foster parents and a physical environment that is practically identical to that of a normal family. The living space, the daily routine and the nature of the relationships are thus closer to the child's normal family life. All this is important for the child's optimal development and the satisfaction of his/her basic needs in life, including social needs. However, despite all efforts, there are certain specificities in the behaviour, relationship to authority and rules of foster children.

This text describes how these specifics of children from foster families are perceived by nursery schoolteachers.

2. Literature review

Substitute family care has undergone significant changes during its development. The works of Matějček, Langmeier and Dytrych [5; 6; 8; 9; 10; 11; 12] were of great importance. Already in the 1970s, they were intensively engaged in the psyche of children from substitute care. They pointed out the unfavourable conditions of institutional care in infant institutions and orphanages and emphasized the need for an intimate environment that allows the child to establish a firm and deep relationship with the caring person. They emphasized that suitable conditions offer different forms of substitute family care. However, the basic principles of foster care as we know them today did not begin to take shape until after 1989.

Foster care can be defined as: «a form of substitute family care in which such are placed children who cannot be taken care of personally by their parents for short-term or potentially long-term reasons 2» [16, p. 11]. The court decides on the placement of the child in foster care. It is a «type of state-guaranteed and controlled form of substitute family care» [4, p. 21]. Foster care is also terminated by the court's decision. In addition to the possibility of a court decision, foster care ends when the child reaches the age of majority (18 years), gets married or when the foster parent or the child dies. In practice, we also encounter situations where the child expresses the wish to remain with the foster parents even after reaching the age of majority. In such a case, the child continues to receive an allowance to cover the child's needs and the foster parents are remunerated until the child reaches the age of 26, i. e., similarly to the case of ordinary family care [17].

Defining a foster family is not easy. A number of aspects enter into the issue which prevent the creation of a clear definition. Koluchová & Matějček [5, p. 89] perceive the foster family «as any other, that is, an extremely complex and dynamic unit with its specific features and problems». Although this definition is outdated, it is worth noting the emphasis on the similarities between foster and biological families.

According to Zezulová [19] a child goes through three phases after entering a foster family. In [1] the getting-to-know-you phase, children seek security and strive to anchor themselves in their new family. The child seeks a person who can meet his or her needs. This period requires a great deal of patience from the foster family and the child and limits frequent changes of environment (visits, etc.) to successfully adjust to new faces and new surroundings. For [2] the release phase, testing of set boundaries is typical. One of the common phenomena of this phase is dependence on the foster mother [3]. The acceptance phase is the imaginary end of the process. In this phase, the child becomes acquainted with his / her new family, knows his / her role and position in the new environment, and knows what to expect. If the child is accepted by the family without reservation just the way he or she is, the child accepts his or her new family and deep emotional relationships can be formed.

John Bowlby's attachment theory can be successfully applied to the situation of finding and establishing a relationship between a child and foster parents. It is «an innate system, inherent in humans and many mammals, which binds the young to the parent or caregiver because they find security, reassurance, and support in their proximity» [1]. Safe attachment is essential for successful foster parenting and healthy child development [15]. This is typically found in situations where foster parents meet the child's emotional and social needs and the child feels accepted, understood, and valued. In the case of problematic acceptance of the child by the foster carers, the bond between the child and the foster carers may become distant, ambivalent, or disorganised. All three types of attachment present obstacles to the child's adaptation to the foster family and complicate the child's continued functioning together in the foster family.

Despite the foster parents' best efforts to meet all the child's needs, to accept and understand the child unconditionally, and to respect the child's specifics, experts describe some specifics in the behaviour of children from foster families. According to [19], common manifestations of children include affective behaviour, purposeful behaviour, refusal of food or joint activities and sibling rivalry. The author states that the child tries to show that he or she is dissatisfied with something or is unable to express him or herself in any other way. However, in addition to these common manifestations, it is possible to encounter more serious manifestations that may be the result of previous experience or the current situation in the foster family (especially in response to an unsatisfactory relationship between the child and the foster parents). In this context, Zezulová mentions developmental regression, deprivation symptoms, problem behaviour (typically stealing, lying, or cheating) and affective behaviour.

A nursery schoolteacher may also encounter similar manifestations in a foster child. It is difficult for a child to find a firm place in the family. Nursery school is another new, unfamiliar environment for the child, to which he or she must adapt and establish a firm position in the peer group H. Pazlarova [13] therefore recommends that foster carers consider taking their child to nursery school3. According to Grohová [2], these children may enter nursery school with a broken emotional attachment. This may result in psychological deprivation or a weakened identity of the child. In this regard, the KITS intervention seems to be beneficial for the child. It aims to support the child's emotional development, their ability to self-regulate behaviour, and develop social skills and early academic skills necessary for success in nursery school. Although it is a costly program, Lynch, Dickerson, Pears & Fisher [7] document the high effectiveness of such resources.

The specifics of the child's behaviour mentioned above may affect the child's socialisation process. Helus [3] refers to socialization as the process of an individual's integration into relationships with people, social groups, society, or a socio-cultural system. The possible effects of specifics in the behaviour of children from foster families can be seen in the child's relationship to the norms that are presented to him or her. Vágnerová [18] adds that changes in socialisation cannot be seen only as a change in external manifestations (behaviour), but also in internal manifestations such as the child's self-concept and experience. From the social group, the child expects a certain disposition of characteristics that make him / her able to identify with it and satisfy his / her needs [14]. Clearly, the peer group represents an important frame of reference for the child.

3. Methodology

In 2021, research was conducted at Tomas Bata University in Zlín, Faculty of Humanities, focusing on specific manifestations of children from foster families in the nursery school environment

Research objectives and research issues

With regard to the focus of the research, the main objective was to explain selected specific manifestations of children from foster families in the nursery school environment.

The main objective was specified by the following sub-objectives:

‒ to describe the behaviour of a foster child towards a nursery schoolteacher;

‒ to reveal the relationships of children from foster families with their peers in the nursery school environment;

‒ to analyse teachers' experience with children from foster families.

The main research question emerged from the research objectives: What are the selected specific manifestations of children from foster families in nursery school?

The sub-objectives have been set as follows:

‒ how can the child's behaviour towards the nursery schoolteacher be characterized?

‒ what are the relationships between children from foster families and peers?

‒ what is the experience of teachers with children from foster families?

The Research Set

The research sample consisted of 5 nursery schoolteachers with professional experience with children from foster families. Due to data protection and the difficulty in accessing teachers with the necessary experience, it was not easy to secure the necessary participants. Therefore, the snowball method was used. Each participant was informed of her anonymity and informed consent was obtained from her.

Next, we will briefly characterize the participating (P) of research.

P1: 12,5 years of experience in nursery school; experience with 2 children from foster care (currently working with these children).

P2: 5 years of experience in nursery school; experience with 2 children from foster care (currently working with these children).

P3: 25 years of experience in nursery school; experience with 5 children from foster care, currently working with 1 child.

P4: 6 years of experience in nursery school; experience with 3 children from foster care, currently working with 1 child.

P5: 15 years of experience in nursery school; at least 1 child from foster care in each year of his practice, currently working with 2 children.

Methods

An individual semi-structured interview was used for data collection. The interview focused on the following areas:

‒ the general characteristics of a child in a foster family;

‒ the child's adaptation to nursery school;

‒ the child's functioning in the nursery school community;

‒ the authority of the nursery schoolteacher;

‒ the child's awareness of foster care.

Due to the pandemic situation, it was necessary to use remote communication (Skype and Messenger) to conduct the interviews. According to the participants' possibilities and willingness, video chat was preferred to better capture the manifestations of nonverbal communication. The length of each interview ranged from 20 to 30 minutes.

The collected data were analysed through open coding method.

4. Results

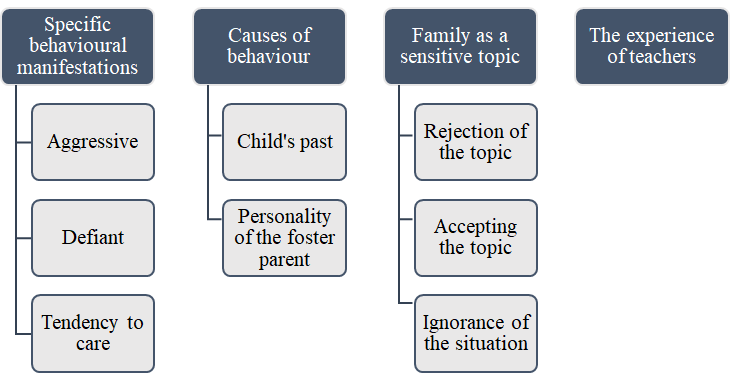

The analysis of the collected data revealed four main categories, which were further subdivided into related subcategories (figure 1). In the following lines, each category will be thoroughly described.

Fig. 1. Diagram of categories and subcategories

Specific behavioural manifestations

Aggressive behaviour

From the teachers' testimonies it emerged that they most often encounter manifestations of aggressive behaviour among children in foster care. According to the teachers, these manifestations were related to the child's previous experience or resulted from a change in the child's life situation ‒ his / her entry into a foster family. Aggressive manifestations occurred during spontaneous play or were a reaction to a required change in activity, in which the child wanted to continue. Impulsive and explosive behaviour was observed in conflict situations with other children, sometimes even in relation to teachers. Verbal aggression, kicking, scratching, or biting appeared towards the teachers. «He expressed himself only by beating someone, punching someone, breaking something, throwing something around, verbally. Whatever the teacher wanted him, he only did was kicking, scratching, biting the teacher» (P5). In this particular case, it was a response to a change in the situation in the family. The biological mother had applied to have custody reinstated. Those manifestations became intense after every contact with the mother. Other teachers also mentioned the children's aggressive behaviour. It can be assumed that in most cases they were a means of releasing psychological tension or were a manifestation of an unsocialized attempt to communicate with others in the class.

Defiant Behaviour

Children's defiance was most often manifested in the areas of disrespect for rules and norms, willingness to cooperate with the teacher, and in eating. «She is very I would say almost like defiant and doesn't want to cooperate» (P4). Teachers mentioned a link with situations where the child felt the need to draw attention to himself or herself by public defiance or to define himself or herself against the teacher's authority. In the case of refusal of food, the teachers attributed the cause to a protest against a certain situation (either in relation to the child's overall situation and his / her placement in a foster family or directly in relation to attendance at the nursery school).

Tendency to care

An interesting manifestation that was often mentioned by the teachers was the tendency of the child to care for other, especially younger children in the class group. Regardless of the relationship he or she expressed with the older children or the teacher, they were affectionate towards the younger children, helping and defending them. For example, Teacher P1 stated that in her experience, children from foster families «tend to look after the younger children, help those children». «he was totally welcoming younger children, he would even hug them, sometimes too much. His warmth was great on this side» (P5). In some cases, the condition was not the younger age, but situations where another child was sad: «…he is overly empathetic, if someone is sad he goes to ask why or what actually happened» (P5).

Causes of behaviour

According to the participants, the teachers see the causes of these behaviours in two areas: The first is the children's previous experience in their biological family. Often these were children of parents addicted to alcohol or drugs, children who had experienced neglect, abuse, or various forms of threat to child development through inappropriate behavioural patterns. Teachers cited the children's reaction to the current change in their life situation as another cause. This was most often the placement of the child in a foster family, change of foster parent or contact with the biological parent.

Child's past

In their accounts, participants had problems with children coming from drug addicted families, a child abandoned in a baby box who also spent time in an orphanage, a socially neglected child, or a child whose current foster care was changing. Most of these children exhibited aggressive behaviour, which I will discuss under the category of Specific Behavioural Manifestations. «Absolutely horrible fate. Dumped in a baby box. Then she took him back and after maybe six months she put him in an infant home. He was just dumped like twice. Just the deprivation was like a significant one» (P1). As a consequence of these changes, the participant even inferred psychological deprivation, which, according to the participant, is common among institutionalized children (note: this is an assumption by the teacher, not a statement by a psychology expert). «Mother a drug addict. She travelled around the country with the boys living in different facilities. The boy stabilized after that. The mother reapplied for the child and the boy went completely off the rails. Behaviour changed» (P5).

Sychrová, in her research on the pedagogical aspects of substitute family care, also sees the causes of aggressive and verbal assault as a previous experience of institutional education.

Personality of the foster parent

According to the participants, the person who takes care of the child is of great importance. Grandparents were the most frequently mentioned foster parents in our research. Placements with long-term and temporary foster carers were less common. In the case of grandparents, participants reported a poor experience and suspicion of providing poor quality parenting to the child. These included loose parenting, poor rule setting, lack of development and problems with excusing foster children. «Very loose parenting by the grandmother. She does not set rules. I think there is a problem with her as if from the home environment» (P4). «I don't think that's where the development is happening. Probably because she is older she does not have as much time, energy, maybe the desire to work with these kids. The excuses were strange. She was always having problems, difficulties» (P1).

Similar findings were also reached by Vanderfaeillie et al. In their study they reported that foster carers' choice of poor parenting strategies promotes the emergence of problem behaviour. Thus, it was the failure of the foster carers, through their inappropriate punishments or inexperience in dealing with problem behaviour, which contributed to the increase in the foster child's internal problem behaviour.

Family as a sensitive topic

The topic of family is a common and necessary one in early childhood education. However, for children with negative family experience, this topic can be problematic. Teachers experienced a reaction of refusal to cooperate when the topic of family was included. For some children, however, the topic of family was not a problem and they talked openly about their experience. Teachers also often worked with children who were not yet informed about their family situation.

Rejection

Many children refused to talk about their family and their experience in the family environment or to do any activity related to the topic of family (thematic drawing, making gifts for parents, etc.). «He didn't mention the family at all. The only one he mentioned was his brother» (P5). If they did talk about family, the children's mood visibly changed. «When we spoke about the topic of family she was obviously downcast» (P1).

Accepting the topic

Some children were willing to talk openly about their biological and foster family without any obvious signs of embarrassment, insecurity, sadness, or other uncomfortable feelings. They even routinely used the term 'mummy' when addressing their foster carers. «She responds well to it, the child herself said she was from the baby house» (P2).

Ignorance of the situation

For some children, teachers encountered a situation where the child did not yet have information about their family situation or did not yet fully understand it. The teacher has to be very careful in such a situation. Only the legal guardian or foster parent has the right to tell the child this information and the teacher must respect their decision.

The experience of teachers

During the interviews, the teachers reported various experience with foster children to which they had to respond and adapt their work to the situation. The more experienced participants were aware of the need to work not only with the foster child but with the whole class. This required specific reactions of these children that were unusual for other children. Thus, teachers had to actively contribute to the integration of children from foster families into the classroom community and help other children to understand the manifestations of these children.

Teachers also mentioned the need for close contact with children from foster families. Although in various situations they were aggressive, refused to work and showed disagreement with the rules, there was a marked need for physical contact, caresses, and cuddles, although they often forced this attention in inappropriate ways. In some cases, the child even developed a very close relationship with the teacher: «If I exaggerate it, she loves me, if I come she hugs me. Every day she asks my colleague when I am coming» (P2).

Teachers often mentioned the experience of children who had been removed from their biological parents. These children came with a history of drug addicted parents. This, according to the teachers, often manifested itself in specific reactions of an aggressive or rejecting type.

5. Conclusion

The main aim of this paper was to explain selected specific manifestations of children from foster families in the nursery school environment. The research showed that although children from foster families perceive the teacher as an authority, they often react with specific behaviours. The most common manifestations include aggressive or rejecting behaviour of the child. Some of the children clung strongly to the teacher's manifestations of affection. There were inconsistent reactions towards other children: In the case of children of the same age or older, aggressive expressions and conflicts were frequent, while towards younger children and children who were currently sad, the children from foster families showed a very positive and warm relationship with a tendency to care for and help these children. Overall, the teachers' experience with children from foster families in the nursery school were positive. They approach the children's unwanted expressions with understanding and similarly help the other children in the class to understand the expressions of these children. In this way, they make a significant contribution to the successful integration of foster children into the peer group and thus help them to overcome barriers arising from their life situation and life experience.

References

- Bolwby J. Separation Anxiety: A critical review of the literature. In: Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1960. 1 : Vol. XLI. P. 251‒269.

- Grohová J. Dítě v náhradní rodině potřebuje i vaši pomoc!: informace a pracovní listy pro pedagogy. Prague : Středisko náhradní rodinné péče, 2011. P. 42.

- Helus Z. Úvod do psychologie. Prague : Grada, 2018. P. 310.

- Collective of authors Dobrý pěstoun: náhradní rodinná péče v ČR. Tábor : Asociace poskytovatelů sociálních služeb ČR, 2018.

- Koluchová J., Matějček Z. Osvojení a pěstounská péče. Prague : Portál, 2002. P. 155.

- Langmeier J., Matějček Z. Psychická deprivace v dětství. Prague : Státní pedagogické nakladatelství, 1963. P. 279.

- Lynch Frances [et al.]. Cost Effectiveness of a School Readiness Intervention for Foster Children. In: Children and Youth Services Review. 2017. 81 : Vol. 6.

- Matějček Z., Dytrych Z. O nevlastních dětech a nevlastních rodičích. In: Československá psychologie. 2000. 3: Vol. 44. P. 193‒201.

- Matějček Z., Dytrych Z. Děti, rodina a stres: vybrané kapitoly z prevence psychické zátěže u dětí. Prague : Galén, 1994.

- Matějček Z. a Dytrych Z. Nevlastní rodiče a nevlastní děti. Prague : Grada, 1999.

- Matějček Z. Náhradní rodinná péče: průvodce pro odborníky, osvojitele a pěstouny. Prague : Portál, 1999.

- Matějček Z., Bubelová V., Kovařík J. Pozdní následky psychické deprivace a subdeprivace. III. část: Děti narozené z nechtěného těhotenství, děti z dětských domovů a děti z náhradní rodinné péče v dlouhodobém sledování. In: Československá psychologie. 1996. 2: Vol. 40. P. 81‒94.

- Pazlarová H. Pěstounská péče: manuál pro pomáhající profese. Prague : Portál, 2016. P. 255.

- Procházka M. Sociální pedagogika. Prague : Grada, 2012. P. 203.

- Schofield G., Beek M. Attachment Handbook for Foster Care and Adoption. London : CoramBAAF Adoption & Fostering Academy, 2018.

- Sychrová A. Pedagogické aspekty náhradní rodinné péče. Pardubice : University of Pardubice, Faculty of Philosophy, 2015.

- Trnková L. Náhradní péče o dítě. Prague : Wolters Kluwer, 2018.

- Vágnerová M. Vývojová psychologie: dětství a dospívání. Prague : Charles University, Karolinum Press, 2012. P. 531.

- Zezulová D. Pěstounská péče a adopce. Prague : Portál, 2012. P. 197.